|

|

|

|

|

Japanese Kumihimo, the Art of Silk Braiding

|

|

|

|

(Summary of several presentations in Germany, i.e. at Deutsch-Japanische Gesellschaft [German-Japanese Society] in Munich and at Fachverband Textil [Textile Society] in Dachau; My thanks to Richard Sutherland and Duane Wakeham for assisting in this translation.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

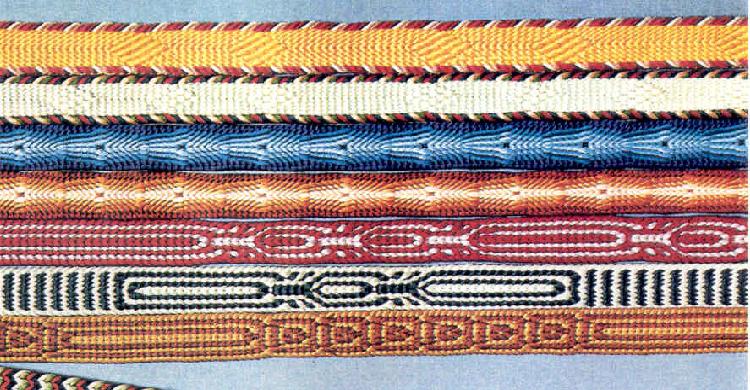

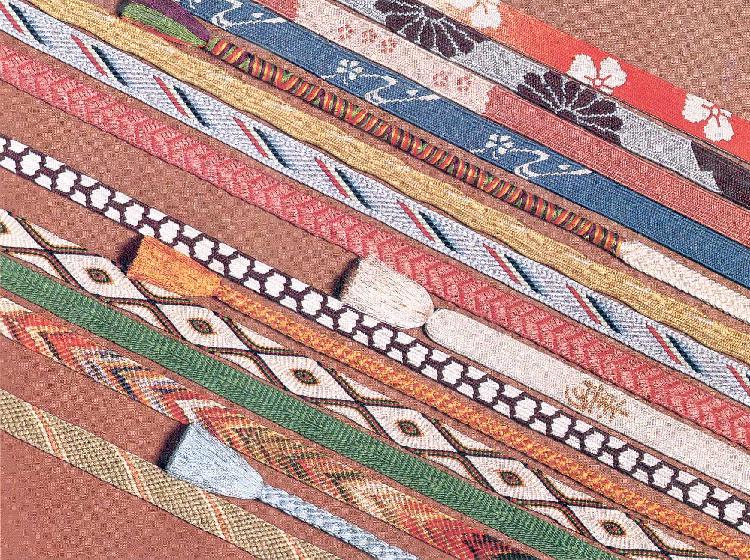

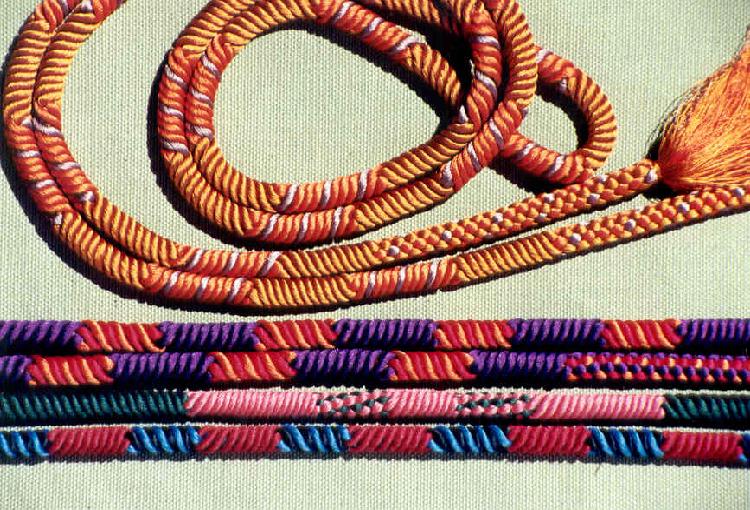

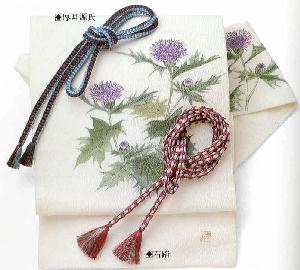

‘Kumihimo’ roughly translates into English as ‘braided cord’. The word has come to represent, in a larger sense, one of the least known of the traditional arts and crafts of Japan. Due to a cord’s small, inconspicuous presence, it is often overlooked, even in discussions related to kimono dress. The ‘obi’, a wide 5 m (15’) long sash, is a substantial component. An ‘obijime’ is required to hold the obi, and everything underneath it, in place, Obijime are usually narrow braided belts, 2.5 m (7.5’) in length (three examples in photos at right).

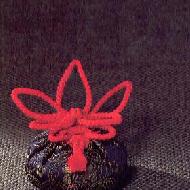

In Japan, braids are also used for religious ceremonies, ornament on festival carts, tea ceremony containers, ribbons for mirrors, fans and inro, and most recently for attaching cell phones to belts, purses, etc. (Examples in photo at right.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Hoko Tokoro Studio; Ogaki´

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Japan braid is often used as closure for clothing instead of buttons (Photo at left).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tea ceremony equipment requires elegant kumihimo for the storage containers. In former times elaborate knotting was a way to prevent the tea from being poisoned, since the knotting was difficult to re-create once it was disturbed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

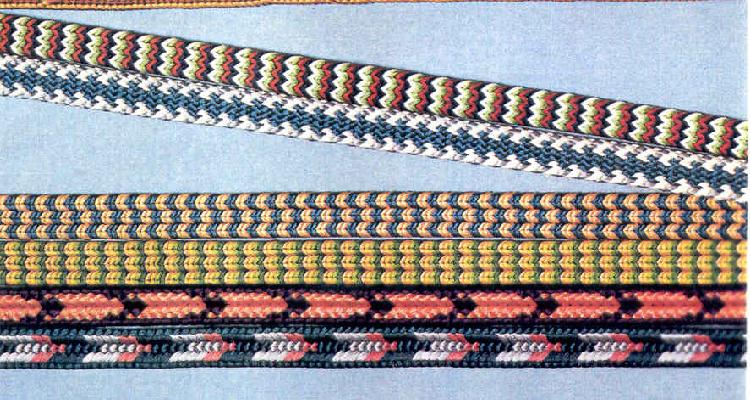

These braids were crafted on different wooden braiding tools

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Toshiko Tanaka; Hanamusubi - Traditional Japanese Flower Knots

|

|

|

|

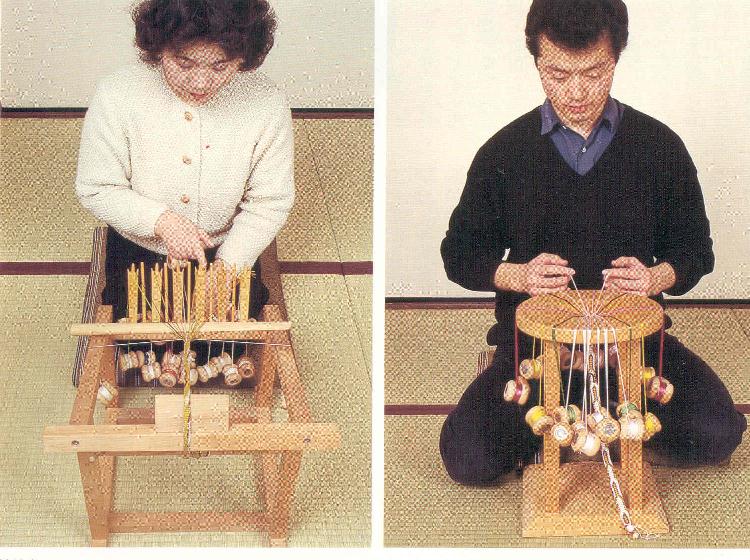

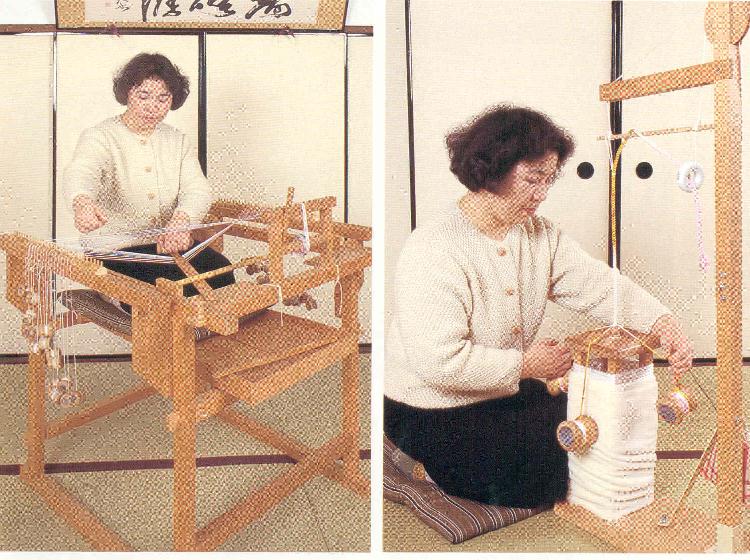

Four wooden stands, or loom-like structures, are the most commonly used method in creating kumihimo.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The basic technology for the four stands is the same. The working arrangement for braiding requires threads that are held under tension. Fine silk threads are bundled and wound around wooden bobbins that are weighted with lead to reach 85 g (3,5 oz) or 100 g (4,2 oz). When braiding on a marudai or kakudai, balance is achieved by the addition of a counterweight that weighs roughly half of the combined weight of all the bobbins used. The bobbins are lifted across the top of the marudai in pairs. There can be as few as four, or as many as is workable. Most Japanese marudai braids, both flat and round, are made with 8, 16, 24 bobbins.

Shown below is a marudai, both before the silk threads are tied to bobbins and with a 42-bobbin braid in process.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then the equipment shown on the right was developed - the forerunner of the Marudai and Kakudai. Very little is known about the history of Kumihimo. Braids are only one small part of the textile tradition and generally are considered insignificant. Documentation was not encouraged. Complex patterns and techniques were passed on verbally in order to keep them secret among family members or guilds, a tradition still practiced by some of the kumihimo schools today.

The period of serious development for today’s common form of kumihimo began in the Nara period (645 - 784 A.D.). Patterns were created in a palette that consisted of lilac, magenta, blue, green, gold, and an orange specially imported from China. This combination was considered powerful enough to banish evil ghosts. There was a saying that women who wear a belt of these ”Shoso-in colors” are protected against bad luck.

During the Heian period (784 - 1184 A.D.) Buddhism became the dominant religion in Japan, opening up a vast market for braiders. Exceptionally beautiful cord of varying sizes was used in temple interiors, and was strictly regimented. Monks did the braiding, which was perceived as a form of meditation. Many of these exquisite braids still exist, often having been hidden away in statues.

A famous braid from the 14th century was found at Saidai-ji, one of the Seven Great Temples of Nara. Originally it took two people to braid it. Photo at right shows a modern reconstruction of the pattern, braided on a takadai using 56 bobbins.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Catherine Martin;Kumihimo - Japanese silk braiding techniques

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The origin of the ”Hirao” belt also can be traced to the Heian period. Made on yet another type of stand called a ”karakumidai,” it is basically a Chinese braiding technique. Only royalty – an emperor, empress, crown prince, and the three highest ranks of noblemen - were permitted to wear a Hirao. The exceptionally wide belt - 15 - 25 cm. in width; 250 cm. (8.3’) in length - is folded three times and wound around the body with the ends hanging down the front. Pictures of these belts unfortunately must not be shown

.Photo at left shows some of the patterns used for these treasured braids, which are allowed to be shown in public.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The photo at the right shows more reproductions of the ”kikko” pattern. In samurai times, the armor braids were placed in iced water for 24 hours to make them more resistant by tightening them. (The new braids in the photo, however, have not been iced). The strength of braid is phenomenal. In order to cut these ribbons you must be a very good sword fighter - and of course have a very sharp sword. With a tightly braided cord you can tow a car.

|

|

|

Edo print of a seller of braids in a Kyoto shop

|

|

|

Source: Catherine Martin; Kumihimo

|

|

|

The Monoyama period (1573 - 1614) is the beginning of the kumihimo of today. It evidenced change in kimono style with the introduction of a very wide ”obi” (sash) that required a narrow cord to hold it in place. The braided ”obijime” was created for this purpose. The style is still worn in Japan today when wearing a kimono is appropriate.

Toward the end of the Edo period (1616 - 1867), the takadai, or high braiding stand, developed into its current form, one allowing for more complex, intricate patterns to be created.

Edo (later named Tokyo) became the center for kumihimo. Most of the traditional patterns that have become standard repertoire in Japanese braiding were developed during this era and the first books of patterns were published.

By the time of the Meiji period (1867 - 1912) samurai culture had declined and the wearing of armor was prohibited by law. Braidmakers suffered from the loss of samurai business, but gained new employment from the popularity of the kimono cord. They were to be heavily affected, however, by the invention of braidmaking machines and synthetic thread, which permitted production of cheaper braids. Today 95% of the obijime produced are machine-made.

Despite this, there still is a market for expensive, exclusive hand-braided products, especially for obijime. Photos at right and below show some examples.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Schools, Classes

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kumihimo is considered one of the traditional Japanese arts, though it is not as well known (even in Japan) as the tea ceremony or ikebana (flower arranging). Specialized schools have a long tradition and still attract students who want to learn the techniques for life enrichment and enjoyment purposes, rather than as income-producing employment. Usually the students are bound to their school for a lifetime.

Competition between the few remaining schools is strong. Each jealously guard their patterns and techniques. Switching from one school to another is possible only with permission of the ”sensei” (master/instructor). Instruction is firm and strict - also expensive. A certificate of course completion from a school may allow the student to teach, with strict adherence to the school’s curriculum. It also may require a ”kickback” to the school, which is common practice with many art/music schools in Japan.

For kumihimo, probably most well-known is Tokyo’s Domyo School, which at one time had a ”living national treasure” as its master. When the current Empress was Crown Princess, she was a sponsor of the school and a kumihimo enthusiast. The royal ladies-in-waiting visit the most renowned schools each year to purchase obijime for their court appearances.

|

|

|

|

Kumihimo outside of Japan

|

|

|

|

Kumihimo was introduced to the Western world in the 20th century. For Europeans and Americans who wanted to study kumihimo in Japan were confronted with nearly insurmountable difficulties. The schools were reluctant to accept foreigners and for those who were allowed in, there was the language barrier. In spite of this, some were able to find open-minded Japanese teachers, who were persuaded by their seriousness. As interest grew - particularly in the 1970s - some courageous female sensei traveled to Europe and the U.S. to give instruction.

Mrs. Tokoro, my sensei in Cologne, Germany, was one of these women who for more than 25 years has returned every year to encourage her former students and create new ones. In Japan, Mrs. Tokoro began teaching braiding on the marudai to people with physical handicaps as a means of strengthening co-ordination and focusing attention. In Cologne she also has been successful using braiding with mentally challenged children.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Braiding technique

|

|

|

|

There is braid pattern notation, just as there are music scores. Although it may differ from school to school and from sensei to sensei, there are enough similarities that most students can decipher them. Seen at right (top) is a pattern to be worked on a marudai. The placement of the starting threads and the moves are seen as though looking down on the stand.

Below that at right, a takadai ”score” for an irregular pattern that requires 156 steps before it repeats. It is a definite ”mine field” for mistakes of all kinds. An error always (and I stress, always) must be corrected. Some patterns have as many as 400 steps. Unfortunately, one may not notice until step 76, for example, that a mistake was made at step 35. Backing out is a challenge – also a great learning experience.

Kumihimo takes a lifetime of practice and dedication. With time, one’s confidence builds and more challenging patterns requiring more bobbins can be attempted. The most difficult pattern, however, the ”touch-stone”’ of expertise, is a marudai braid created with only four bobbins. Only a true master will be able to make this simple braid perfectly.

A sensei at a famous school explained that the braiding of three silk threads is the truest test of skill. So try to braid a perfect pigtail for 2.20 m (8’) and you will know what the sensei means.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|